A view of Pretoria from the New Zealand Official Residence. © Felix Geiringer

South Africa formally went into lockdown one day after New Zealand.

It was a stricter lockdown than NZ’s. For example, no one was allowed to go outside for exercise. In any case, walking around outside is not considered a safe thing to do here. Parks and playgrounds can be safe if surrounded by a high electric fence with security guards at every entrance, but all such places are closed. Alcohol and tobacco sales were also banned.

Lockdown rules have been enforced by patrols of police and military. In Gauteng (the province containing Pretoria/Tshwane and Johannesburg), there was an effort to round up the large homeless population and move them to makeshift camps in disused sporting grounds. It was not entirely successful.

This might sound extreme to New Zealand ears, but the stakes are much higher here. South Africa had to go harder and earlier. About 8 million of South Africa’s 58 million people are HIV positive. Despite a recent push significantly improving the situation, only about half of those people are receiving effective treatment. That means 7% of the country have severely compromised immune systems, just from HIV..

The living conditions for many South Africans also make social distancing an impossible dream. Over a third of the population live in townships or large squatter camps known as “informal settlements”. Accommodations can range from cramped to, frankly, appalling, and many lack basic amenities.

Aerial View of Diepsloot © Martin Harvey

One such township close to here is called Diepsloot, literally “deep ditch”. A sea of corrugated iron shacks tumble across a wide depression on one side of an extremely poorly maintained road. It was in the local news shortly after we arrived with stories about the appalling condition of its primary school.

Residents of these settlements know about COVID-19 and are concerned about it. But some understandably point out that without a properly functioning sewage system, rubbish collection, or even running water, they have more pressing health problems to worry about. It is hard to understand how social distancing is even supposed to work in a place that is that cramped.

There are also economic obstacles to an effective lockdown. Many people live a literal hand to mouth existence. On days when they fail to find work, they do not eat. People may understand the importance of the lockdown, may believe in the need for it, but still break it because they have to.

Mobile testing facilities have gone into some of the townships, including Diepsloot. But even with testing one wonders how to prevent the virus spreading in places like these. A few days ago, a Dieplsoot nurse tested positive for the disease.

So, the fear here is that, without extreme measures, COVID-19 could spread like wildfire here and exact a truly terrible toll.

Luckily, the disease has struck at a time when the country has competent leadership. Internationally, President Cyril Ramaphosa has received praise for his handling of the crisis, both for the country and, as the current president of the African Union, for the whole continent. Action has been reasonably decisive, relatively swift, and somewhat clearly communicated (yet not without humour). Some of Ramaphosa’s playbook was similar to Ardern’s, and maybe there is a reason for that.

His Excellency, @CyrilRamaphosa, shook both our hands. He had a broad smile and was very welcoming. He told me that he was a big fan of @jacindaardern and that he would love to come visit New Zealand. pic.twitter.com/XuTXTmpyMR

— Felix Geiringer (@BarristerNZ) January 28, 2020

Thank goodness someone like Thabo Mbeki was not in charge. If you want to understand that comment google “HIV/AIDS denialism in South Africa”.

In short, it feels like the Government here is doing what it can to halt the spread of the virus. However, it is hamstrung by a lack of resources. And the extreme measures that are being taken are problematic. In one incident early in the lockdown, police fired rubber bullets at shoppers who were failing to adhere to social distancing rules.

Long before COVID-19, South Africa was in a deep economic crisis. The country is practically broke. South Africa desperately needs massive infrastructure investment. But the country was told that unless it took an axe to public spending in the last budget, Moody’s would downgrade its Sovereign status to junk – significantly worsening the financial crises. Standard and Poor’s and Fitch had already done so. Cuts were made, COVID-19 hit, the lockdown was announced, and Moody’s downgraded South Africa’s status anyway.

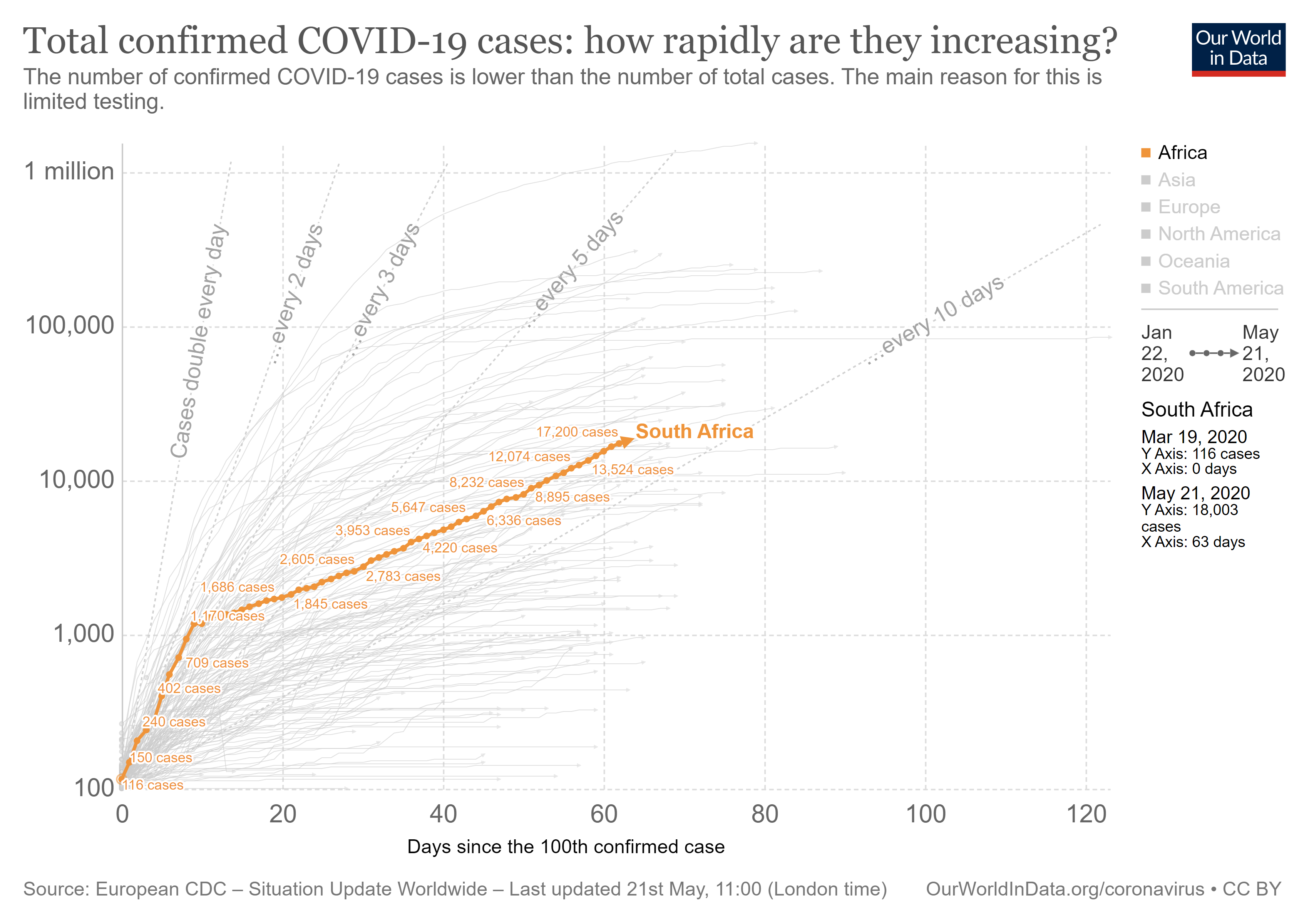

What this all means is that the goal is more modest here. The lockdown (and especially the ban on international travel) flattened the curve as the dent in the graph shows. However, confirmed cases are still increasing exponentially, just with a smaller exponent. There is no expectation that it can turned around.

The lockdown has therefore been declared a success and it is being slowly relaxed. It is now lawful for us to go for a walk (between 6 and 9 am), or buy clothes, and restaurants are open for deliveries.

It has been a success. The lockdown delayed the spread of the virus and bought the country time it desperately needed to gear up hospitals. Ramaphosa says it has saved tens of thousands of lives. I believe him. What I fear is that that doesn’t mean that tens of thousands of people are not still going to die.